Monkey embryos have recently been used in an experiment with human cells to create man-monkey chimeras.

Scientists have been combining cells of different animal species since 1969, when the French biologist Nicole Le Douarin first created quail-chicken embryos, although the experiments were limited to creating animal chimeras.

In recent years however, various researchers around the world have been creating partly human chimeras. For example, human cells were incorporated into pig embryos in 2017 and into sheep embryos in 2018.

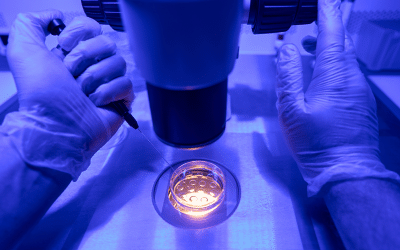

Stem Cell Reports has just published the results from the only team in France conducting research on chimeras. In this experiment scientists injected human cells known as induced pluripotent cells (iPS), into a closely related primate, macaque monkey embryos, which then developed in the laboratory for three days. These iPS cells are differentiated human cells that have been reprogrammed to regain their former non-specialized state as pluripotent stem cells, so they can become any kind of body tissue. The team compared mice and monkey embryonic stem cells which are naturally pluripotent to human cells which had been reprogrammed to be pluripotent, which were injected into rabbit and monkey embryos. The results demonstrated that when mouse stem cells were injected into the embryos, they all became chimeric (the cells “mixed together” continued embryonic development). However, when the embryos were injected with human or monkey embryonic stem cells, only 20-30% became chimeric; integrating only 2 or 3 of the human or monkey cells.

Almost simultaneously researchers in the U.S. and China also announced in the magazine Cell that they had created embryos by combining human and macaque monkey cells. They studied the survival of these human-monkey chimeras for a period of 19 days, the stage at which the primate nervous system begins to develop. Six days after the monkey embryos had been created, each one of the 132 embryos was injected with 25 human pluripotent stem cells. After 9 days, half of them were chimerical, but after 13 days only a third of them remained chimerical. Survival continued to decline until day 19, when only three chimeras remained alive. The overall results can be considered rather poor, since there were only 5- 7 % of human cells in the chimera.

In France, the law prohibits creating transgenic embryos and chimeras, although it could soon be authorized in article 17 of the pending bioethics bill whereby animal embryos could be injected with human embryonic cells or iPS cells. One amendment even considered allowing female uteruses to be implanted with these embryos to give birth to “baby” human-animal chimeras. Although the National Assembly has endorsed, the Senate has voiced its opposition.

The reasons given for continuing this research are more or less obscure, misleading or illusory. Some dream of manufacturing human organs in animals, to provide grafts for transplants. Pierre Savatier, a researcher at INSERM, (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research), who leads the French chimera research and advocates the authorization of such practices, acknowledges that it is a “science fiction scenario”. French law prohibits creating chimeras, but since the 2011 bioethics law did not anticipate specifying the use of iPS cells, this research team nonetheless continues its experiments, considering that what is not specifically forbidden is allowed…

Pierre Savatier declares that “the first major areas that could benefit from this research are reproductive medicine and cell therapy, particularly in the fight against cell degeneration. Currently, it is obvious that improvements in the knowledge of human embryo development is essential, in order to improve assisted reproductive technology (ART) for in vitro fertilization.”

Very few teams around the world are working on this particular type of research and although they are still in the phase of early development, the Council of State has already published warnings of the “risks associated with violating the red line between man and animal” in its’ 2018 report. “There is a risk of creating new zoonoses (infections transmitted from vertebrates to humans and vice versa); the risk of human features and even human consciousness in animals (if the injection of human cells induces changes in animals, for example by cell migration to the animal’s brain, where it could lead to the development of consciousness with human characteristics.)” Finally, another risk to be taken into account is that human cells could differentiate into gametes (sexual cells) in the animal embryo.

These experiments cross the natural inherent boundary line between humans and animals and pretend that there could be no limit, based on so-called superior ethical reasons, imposed on scientific research.